Why can’t we control coccidiosis?

The modern poultry industry isa testimonial to the successful blending of scientific research, innovative business developments, and marketing. The ability to grow poultry faster and more cheaply in many developed countries has resulted in a product that was one of the most expensive meats 50 years ago becoming the least expensive. However, the rapid increases in efficiency of production have not been without costs.

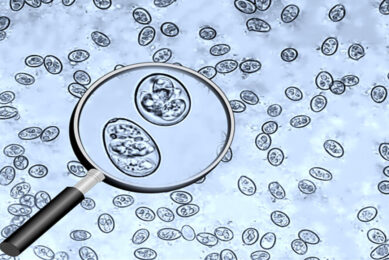

The modern broiler or layer chicken is a delicate organism, easily affected by any slight imbalance in diet or environment. We may not often face problems of extensive mortality in today’s production facilities, but losses in weight gain and efficiency of feed conversion can be devastating economically. It does not matter if we look at the large confinement operations or small flocks in range conditions; coccidiosis is an ongoing, often increasing problem. In discussion the methods available for the control of coccidiosis, we also need to examine the reason why control is difficult. This involves not only problems related to the control methods themselves, but the complex actions of a variety of internal and external factors that influence the severity of the infection in the birds and the adverse effects that result.

A nutritional disease

We need to remember that, first and foremost, coccidiosis acts as a nutritional disease. The best formulated ration will not produce the desired results if the birds cannot utilise the nutrients the ration provides. Nutrient utilisation in any animal involves a series of steps including ingestion, digestion, absorption, transport, storage and metabolism. Numerous studies over many years have documented that coccidiosis can adversely affect all of these stages in nutrient utilisation. The mechanisms involved range from simple destruction of the absorptive mucosal surface to complex interactions involving competition for micronutrients that result in metabolic imbalances. The importance of the nutrient state of the birds should not be underestimated when considering the potential effectiveness of control measures.

Numerous reports show intricate relationships among nutrition, immunity, disease and growth, For example, vaccination which produces immune stimulation may result in a measurable growth depression and poorer feed efficiency, even in the absence of exposure to the disease. Successful immunisation programs for the control of coccidiosis will require that the birds be genetically nutritionally immunocompetent.

Response to an infection

We have long been aware that various nutrient levels in the diet, such as vitamin K, vitamin A and protein levels, may alter the response to the coccidial infection. Recent studies have shown that even the source of the nutrient or the addition of some dietary supplements can affect the severity of the infection. For example, it has been shown that omega-3 fatty acids reduced the effects of Eimeria acervuline and E. tenella infections and that the addition of betaine to the diet improved the efficacy of salinomycin. Other workers have even suggested that the form of the diet or the availability of grit can affect the infection. When I began research on coccidia over 25 years ago, I was told that a producer did not need to worry about coccidiosis in birds less than 2 weeks of age or in older birds as both were refractive to infection.

Furthermore, it was stressed that, even if infected low levels of coccidiosis were “sub-clincical” and produced no economic effects. Both of these widely held ideas are incorrect. Newly hatched chicks are susceptible to coccidial infection. Numerous studies have shown that low levels of infection can cause significant effects on body weight and fee conversion in the modern broiler. Furthermore, one should always be aware of the significant presence of multiple diseases that produce disease interactiions.

Coccidia have been shown in both laboratory studies and field cases to interact with a variety of other infectious agents or toxins in poultry – including bacteria, viruses, mycotoxins and nematodes. In the most striking examples, significant effects on production parameters were demonstrated when the 2 diseases were present together, even though no significant effects were seen with either condition alone. Furthermore, the interactions can sometimes be synergistic and exceed the sum of the effects for the individual diseases.

Problems worsened

When the ionophore anticoccidials, particularly monensin, first appeared on the market, there was a feeling that our problems with coccidiosis were over. During the early period of the use of this group of anticoccidials, growth and feed efficiency reached levels previously unrealised because we had never before controlled coccidiosis to such an extent. It was many years before the first hints of reduced control started to appear in the field. The situation worsened as “reduced sensitivity” and then outright resistance was found in more and more locations throughout the world.

Over the last several years, drug resistance in the US has become so widespread that, in some broiler complexes, no anticoccidials show more than limited efficacy even against moderate infections of the present coccidial strain. Disastrous results have generally been avoided, not because we have developed totally new effective control measures, but because developments in management, especially advances in ventilation and watering systems, have reduced the exposure to coccidia in the poultry house. Sensitivity testing is the only way to ensure that the medication program selected will be effective if conditions arise that result in an increased exposure to coccidia.