Novel approach to reduce cold stress in layers

A new study shows that a warmed perch system, as a thermal device, improves hen health and welfare by reducing cold stress-associated adverse effects in laying hens. Providing warm perches for laying hens has beneficial effects in terms of maintaining body temperature and feed intake without compromising body weight, egg production and egg quality under cold conditions.

Besides the frequent and intense heatwaves caused by global climate change, extremely low temperatures during the winter months have also been observed. In laying hens, a cold temperature is a common environmental stressor that manifests through increased feed intake, along with compromised health and egg production; all leading to economic losses. Environmental and heat transfer data show that laying hens lose about 4 times more energy during cold weather to maintain their body temperature. The detrimental effects of cold stress on hens can be even more severe towards the end of lay when hens have lost a considerable amount of their plumage cover.

Common methods used to prevent cold stress, such as reducing ventilation and increasing the ambient temperature (usually by using gas heaters), present challenges due to poor indoor air quality, posing a threat to bird and caretaker health. Poor air quality due to reduced ventilation and high temperatures in the barn facilitate the build-up of ammonia and dust, leading to increased susceptibility to disease.

Perch system study

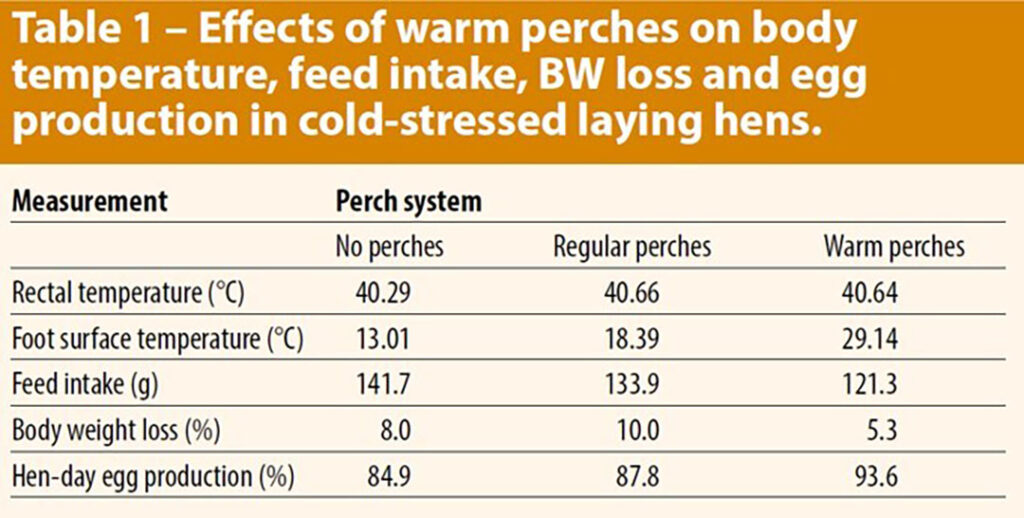

The aim of this study was to examine if a warmed perch system, as a thermal device, could reduce cold stress-related adverse effects in laying hens. At 32 weeks of age, 72 laying hens were randomly housed in 2-bird cages arranged in 3 banks and then assigned to 1 of 3 treatments: (1) warm perches (perches with circulating warm water at 30°C);( 2) regular perches; and (3) no perches (Table 1).

The trial was for a 21-day period. In the warm perches trial, 2 temperature detectors were installed in the 2 loops to measure the supply and return water temperature. Similarly, a single point for the regular perch was also measured. Cold stress was set at 10°C and the ventilation system was fully operational throughout the entire experimental period. Feed and water were provided ad libitum.

The trial was for a 21-day period. In the warm perches trial, 2 temperature detectors were installed in the 2 loops to measure the supply and return water temperature. Similarly, a single point for the regular perch was also measured. Cold stress was set at 10°C and the ventilation system was fully operational throughout the entire experimental period. Feed and water were provided ad libitum.

Perching behaviour and thermoregulation

The warm perch system was found to be better compared to either the regular perch or no perch system in terms of perching behaviour and thermoregulation. The foot surface temperature of hens standing on warm perches was higher than the hens roosting on the regular perches. Rectal temperature was also higher in both the warm perch and regular perch system than with the no perch system. A greater proportion of birds in the warm perch system exhibited perching behaviour than the birds with the regular perch system.

To evaluate how the differences created by the 3 perching systems affected thermoregulation, the researchers measured plasma concentrations of 2 thyroid hormones (3, 3’, 5-triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4)). Thyroid hormones are actively involved in the regulation of thermogenesis and energy metabolism. Cold exposure has been shown to enhance the conversion of T4 to T3 to increase heat production in birds. In this study, T4 was higher in both the warm perch and no perch groups than in the regular perch group.

The researchers noted that: “The provision of warm perches could allow the chickens to gain heat from the warmed perches which, in turn, reduces the need for endogenous heat production from the conversion of T4 to T3. Therefore, the higher T4 in the hens using the warm perch system can be considered an indicator of an ameliorated stress response further to the provision of warm perches. While the higher T4 levels found in the no perch hens probably resulted from the increased metabolic and digestive heat resulting from the excessive feed intake that was observed in that group”.

Egg production and egg quality

Looking at several studies, low ambient temperatures in laying hens lead to an increase in feed intake, while egg production, egg quality and feed efficiency decrease. In the current study, under the conditions of full ventilation and low ambient temperature (10°C), when compared to the other 2 groups of hens, the provision of warm perches prevented an increase in feed consumption while body weight and egg production rate were maintained.

Egg production and quality are closely related to circulating calcium availability. During exposure to cold, chickens experience vasoconstriction which reduces the flow of an adequate blood supply to the gut and uterus – impairing nutrient absorption and eggshell calcium deposition. In this study, eggs collected from hens in the warm perch system had thicker eggshells than those from both the regular perch and no perch systems by the end of the 3-week trial period. The researchers concluded that installing a warmed perch system for laying hens enables the birds to cope better with low ambient temperature and utilise calcium better during eggshell formation. Other egg quality measurements did not differ between the 3 perch systems.

Immune regulation

Prolonged exposure to environmental stressors can weaken the immune system, leading to immunosuppression. Studies in chickens have reported that cold stress decreases the number of lymphocytes which leads to an increased heterophil to lymphocyte ratio which has been used as a stress indicator in chickens.

For immune regulation, the researchers in this study measured plasma concentrations of cytokines, interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-10 (IL-10). IL-6 promotes the migration and proliferation of both T and B lymphocytes. Their results showed a higher peripheral IL-6 level in the warm perch system compared to the regular and no perch systems when hens were exposed to a cold ambient temperature for 3 weeks. “This signals the contribution of prolonged cold stress to immunosuppression in the regular perch and no perch groups of hens, while the provision of warmed perches cushions the negative effects of a low ambient temperature”, they concluded.

Perches for different growth phases

It was concluded that the provision of constantly warmed perches assists laying hens with thermoregulation during exposure to the cold, as indicated by the measured outcomes of feed consumption, bodyweight loss, rectal temperature, foot surface temperature, egg quality traits, thyroid hormones and immunoregulation. The researchers commented that: “The results show that the use of a warmed perch system could provide a novel thermal device to help reduce cold stress during the winter season without compromising air quality in the poultry house. Considering the variation in plumage cover observed in laying hens with age, this study also provides insights for examining the effects of a warm perch system on the different growth phases of laying hens under various cold conditions”.