Cameras offer individual carcass analysis

Elanco, through its knowledge transfer business EKS, is beginning to use imaging to analyse the condition of individual birds in the slaughterhouse. With that data and information from the farm and veterinarian combined it hopes to revolutionise health management, as Poultry World discovers.

The camera cannot lie, or so the saying goes. CCTV in slaughterhouses is usually something tied to ensuring the best welfare for animals in their final moments, but training imaging technology on the birds’ carcasses themselves is offering new insights into bird health and farm management.

Elanco Knowledge Solutions (EKS), working with German technology firm E+V (pronounced E plus V), is helping its customers integrate carcass analysis into poultry production using high-resolution cameras that can map the weight and condition of each individual birds.

“We already had access to customers’ health data and production data – now we’re adding a big piece: the carcass,” explains Kevin Watkins, a founder of EKS. The company was created10 years ago and focuses on adding value for customers beyond the core products that Elanco offers.

Dr Watkins explains the greatest opportunity in this respect was enhanced use of data. “The poultry industry has a lot of data, but we found our customers don’t always have the time or the wherewithal to use those numbers for real decision making, or they didn’t have the ability to integrate everything.”

In focus

Camera technology has long been in operation in red meat and pig plants, where grading carcasses is more important. E+V has equipment in about 20 of the largest beef plants in the States, and capture images of up to 80% of cattle slaughtered in the USA. They are also present in the EU and South America.

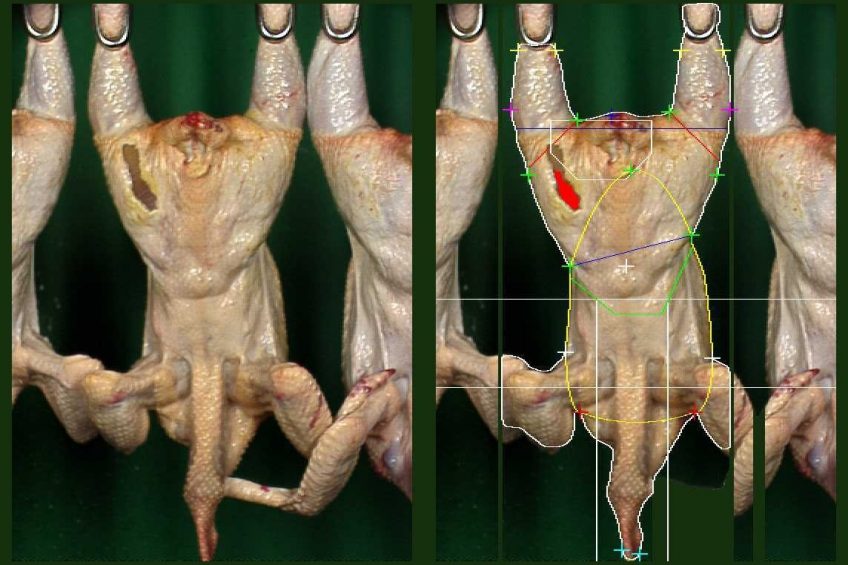

For poultry, the technology is engaged principally in estimating bird weight, and is typically installed after birds are stunned, killed and plucked. “We look at shapes, dimensions and distances, and using those measurements we can predict the liveweight,” explains Dr Watkins.

While that may seem like a basic measurement, many companies rely only on the weight of the incoming truckload of birds; individual measurement gives a differential, or the spread of weights, within a flock. “That’s very important from an analytical perspective,” he adds. A further calculation can go further to estimate breastmeat yield.

The system can currently predict weights at around 94% accuracy when lines are running at 140 birds/minute.

Another feature is the ability to quickly detect visual defects such as skin tears, broken wings, blisters or bruising. And in some cases light filtration can be applied that identifies flaws the human eye cannot detect.

An optional third camera, which has been installed more in European operations, can score the condition of footpads (or paws, as they are known in the US). The measurement can be tailored to whatever scoring system the country or company requires and it again means each individual bird is scored, where before a sample of, say 100 birds, might have been taken.

Furthermore, there’s the potential to mechanically separate footpads that are good enough for human consumption down the line.

The technology also affords greater analysis of slaughterhouse performance, birds only shackled by one leg, for example, are easily identified.

Even this step towards using more real-time data so that errors can be found exactly when they happen – adjusting a scalder tank cannot wait if it is at the wrong setting.

Operational vs analytical

So far, the technology has been mostly used to monitor the outcome of the poultry farming process – carcass weight and quality. But where Dr Watkins sees the most potential is in using these results for feedback and to inform farm management.

“We know that getting chicks off to a good start can actually affect the value of that carcass at the end, we know how health and management can affect things like footpad lesions and the air quality and litter quality.

“We also know the transport process is really critical, the distance and how birds have been handled. Now we can match this data up and start affecting change back where it all gets started. Over time, as we generate more data we’re providing those links.

“We’re just starting to scratch the surface, working to get more people to the place where they see the value in capturing the information and linking it together so we can see a holistic improvement in the entire operation.”