In-ovo feeding can programme performance

The next major advance in poultry nutrition will come from feeding chicks in-ovo, and ‘imprinting’ behaviour through tailored diets in the first days of life.

Making the most of broilers’ genetic potential will mean rethinking the role of the hatchery, according to a leading poultry nutritionist. Peter Ferket, a professor at North Carolina State University, says that in-ovo feeding, as well as offering birds feed as soon as they hatch will become necessary if farmers wish to keep progressing growth rates sustainably. Speaking at the recent ESPN conference, Prof Ferket said that management struggled to keep up with genetic progress. “Genetics is changing the playing field, we cannot deny that. But it’s the expression of genetic potential that’s really driving performance and profits. “We have to consider that birds have unique properties that we haven’t mastered – by the time a new model is out we are still behind. Nutrition and management have barely kept pace with genetics – it’s time to close that gap.”

He explained that, at the rate birds’ genetics were improving, a 4kg bird at the age of 42 days would be possible, with a feed conversion rate approaching 1:1. Prof Ferket said the early life of broilers was the period when performance could best be influenced, both in providing targeted nutrition and “programming” the digestion for later life.

In-ovo feeding, with the nutritional profile of premixes genetically matched to chicks’ needs was one technology showing great potential. His research team had used nutrigenomic techniques to map metabolism at the time amniotic fluid is taken in and designed a pre-mix with energy, vitamins and trace minerals of benefit to the developing birds. The in-ovo feeding had been found to deliver better villi growth in early stages, and improve glycogen deposition in the liver, giving chicks more energy when hatching and in the first hours of life. Subsequently, average bodyweight is improved and skeletal development gets a head start. “It changes behaviour, right after hatch in-ovo-fed birds are more active, inquisitive and eat more feed.” As a result, breast meat yield, growth rates and feed conversion can all be improved.

Programming

Another area of research Prof Ferket had worked on was “programming” birds’ digestion by conditioning the diet in the few days before and after hatch. Nutritional imprinting is the practice of conferring production traits on chicks through influencing the expression of genes. Chicks’ ability to utilise minerals or nutritional energy, or tolerance to immunological, environmental or oxidative stress can all be influenced by early diet.

One example is a study in which broilers were fed a low calcium and phosphorus diet in the first 90 hours post-hatch. At 32 days, those birds are more readily able to absorb those nutrients, and subsequent work has found birds conditioned in such a way are more tolerant to diets deficient in the minerals. “Chicks that have been fed the appropriate conditioning diet, followed by a complementary growing and finishing diet, have improved growth performance and feed efficiency through to market age.”

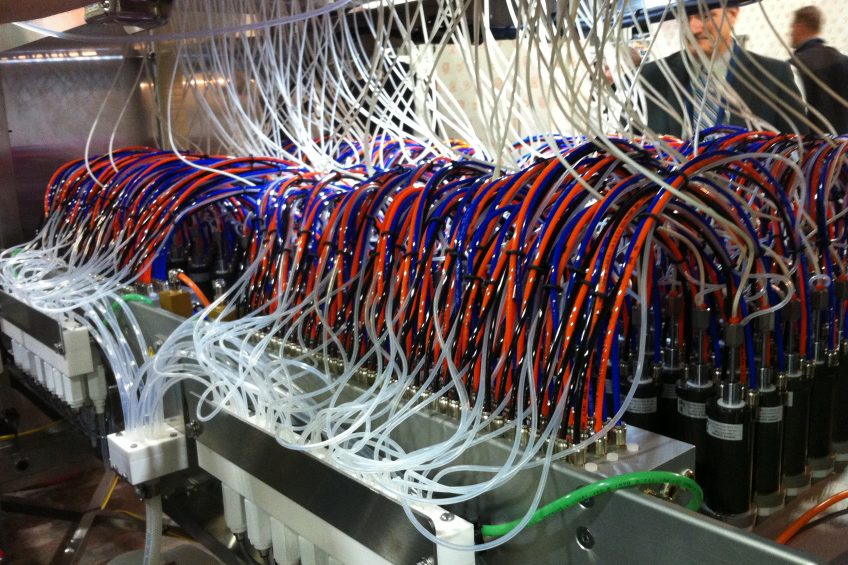

But feeding such a diet can be a challenge with current hatchery set ups. Prof Ferket said one such system, Hatch Brood from Dutch company HatchTech was one example. “The hatchery of the future will be a place that will do much more than simply hatch and vaccinate chicks: it will also be the place where the chicks will be conditioned to better tolerate the challenges of life, and be programmed for optimum nutrient efficiency.”