Key facts about coccidiosis

Keeping on top of coccidiosis is crucial for the welfare and performance of a poultry flock, as Jake Davies discovers.

The cost of coccidiosis to the poultry industry is massive. A 1999 paper put its global cost to production and control at more than $5bn each year. Subclinical cases will hit profitability through poor feed conversion, while damage to the gut wall makes it easy for more virulent challenges to take hold, like necrotic enteritis.

As such, every farmer should be up to speed on the mechanism that causes cocci to harm birds, and the best ways to prevent it responsibly, according to Monita Vereecken of pharmaceutical outfit Huvepharma. “If you want to control the disease, you need to know the disease,” she says.

Coccidiosis is both host specific and site specific – meaning that individual strains can be relatively easily identified. Indeed, anyone able to dissect a bird can learn the basics, identifying the obvious features of each species in an afternoon.

The sub-species are all part of the Eimeria family, and present in distinct ways. E. tenella, for example, will colonise the ceaca, causing it to swell with blood in the worst cases. E. acervulina is less pathogenic, but can hamper performance without causing any clinical symptoms – and so push up feed costs. It also makes for wetter droppings, reducing litter quality as well.

Lifecycle

“The lifecycle of coccidiosis looks simple, but is actually quite complex,” says Ms Vereecken.

“You have asexual and sexual multiplication, and different stages of the parasite invade and cause damage. That is why you cannot grow coccidiosis in the lab – if you want to perform tests, you have to do it in live birds.”

In essence, birds ingest a sporulated oocyst, which is activated by the warm, humid environment of a poultry shed.

Those little oocysts are exceptionally efficient multipliers – one can become thousands in a matter of days.

They typically take five to seven days – depending on the species – to undergo this reproductive cycle, and while inside the guts of chickens, they will be damaging the gut wall.

Degradation

If left unchecked, cocci populations will simply build and build, causing more and more damage to gut walls.

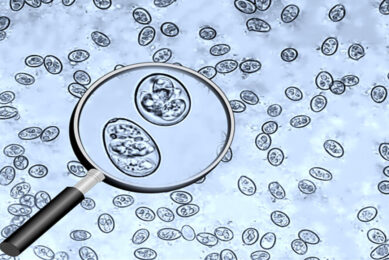

As mentioned, each species has an effect on a distinct region of the intestines (see illustration below).

Detecting the severity and strain of the coccidiosis, fortunately, remains relatively straightforward, using the Johnson and Reid scale.

“It is an interpretive, but fairly standardised method,” says Ms Vereecken.

The first tip she offers is to conduct the biopsy as soon as a bird is killed – E acervulina lesions are so small that they will degenerate very quickly.

“It’s also important to take your time, and look at the entire gut, not just the duodenum.”

As soon as the gut is removed from the bird, the outer wall should be inspected for signs of E maxima, and when eventually opened, care should be taken not to overly disturb the content of the guts as this can provide clues as to how the bird was processing feed.

When in the gut, it’s important to score the highest lesions that you find, and use those to build a picture of the outbreak.

E. acervulina in its most severe form is difficult to detect – the white spots characteristic of milder outbreaks will merge into a white plaque.

“The highest lesions are sometimes the ones that you will miss.”

It also is important not to be too rough with the dissection as it is possible to scrape lesions away while opening the guts.

The purpose of regularly autopsying birds within a flock is to detect whether the control measures – coccidiostats and cleaning regime – are effectively suppressing the health challenge.

Once a representative sample has been taken, a total mean lesion score can be generated that will give some indication of the severity of the outbreak.

Cocci control

|

Coccidiosis – where it colonises (Mouse over icon in illustration below for more information)

Effective health control beats necrotic enteritis

The key predisposing factor for necrotic enteritis in poultry flocks is coccidiosis, but there is a host of other ways the risk of infection can be mitigated.

“You can inoculate a bird with millions of clostridium pefringens bacteria and not see anything,” says Prof Filip Van Immerseel of Ghent University. “The predisposing factors are very important – by eliminating them you can avoid necrotic enteritis.”

The condition is caused by the necrotizing toxin released when Clostridium P overcomes more commensal bacteria in the gut and begins to dominate the microbiota.

Clostridium relies on external sources of protein, so one significant risk factor is high protein diets.

Stress is also a known cause – both heat and stocking density. Necrotic enteritis is almost unknown is low-stocked systems.

Mycotoxins in feed – even below maximum suggested EU standards – have been found to significantly increase the risk of necrotic enteritis.

The disease is also rarely discovered outside of two-to-four weeks, a period in which birds’ immune systems are naturally lower.

Prevention

“The most easy option is to kill the bacteria,” says Prof Van Immerseel. Antibiotics are the only treatment that will destroy the bacteria totally, but there should be an effort to find alternatives to suppress the infection. “Currently there is no feed additive or vaccine that reduces it to zero,” he adds.

Ionophores help, but it is the prevention of coccidiosis that offers the best protection.

A focus for the future of bird health in general will be in ensuring the gut microbiota is balanced, and thereby preventing clostridium gaining a foothold in the gut.

But the key focus for farmers should be preventing the circumstances from which it arises in the first place by using an effective coccidiosis control programme.

*This article is based on findings from a poultry health workshop hosted by veterinary medicines firm Huvepharma.