New and fast detection of Campylobacter

Up to 4 times more chicken flocks show signs of Campylobacter colonisation with the cheap and new air-sampling method presented by an EU consortium. In the future the test could also include sampling of Salmonella, avian influenza or other pathogens.

According to the EU, Campylobacter bacteria caused 246,571 registered cases of foodborne illness in humans in the EU in 2018. This represents 70% of all registered cases of foodborne diseases in Europe in 2018. At the moment, a so called ‘sock method’ for faecal droppings is a common way of testing whether chicken flocks are infected with Campylobacter or not. The disadvantage, however, is that it takes more than 4 days before broiler farmers know whether their flocks have tested positive or not. Being able to identify Campylobacter-positive flocks before they arrive at the slaughterhouse is advantageous because contaminated birds can be slaughtered after negative flocks in order to avoid cross-contamination. At the moment there is no air-based detection method for Campylobacter anywhere in the world. This will be the first ever such system on the market.

Background to the project

The background to this EU project is a new EU regulation which was published in 2017 and requires poultry producers to keep the level of Campylobacter under 1000 CFU/g in the broilers that make it to the slaughterhouse. Professor Hoorfar of the National Food Institute in Denmark explains that the project was initiated “to provide more cost-effective laboratory tools to help poultry producers comply with that regulation.” The new EC regulation from 2017 is an amendment to EC Regulation no. 2073/2005 which brings Campylobacter sampling processes, limits, and corrective actions up to par with those for Salmonella and Listeria, which have both been regulated since 2005.

This is why a new European initiative by the name of OneHealthEJP started the project Air-sampling, a low-cost screening tool in biosecured broiler production. The research work began in January 2018 and will be finalised with guidelines and recommendations by the end of 2020.

European partnership

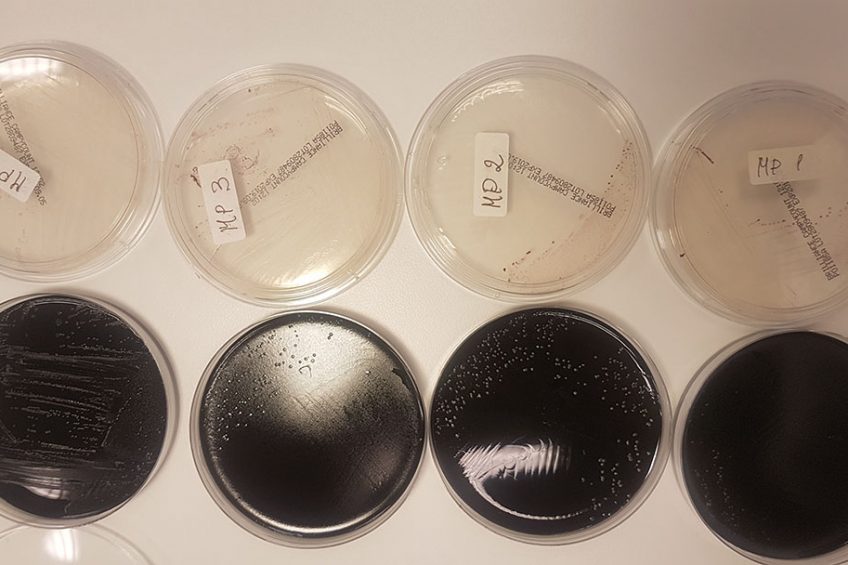

The new air-based method was developed by researchers in the following EU laboratories: National Food Institute in Denmark, Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale dell’Abruzzo e del Molise ‘Giuseppe Caporale’ in Italy, Veterinary Research Institute in the Czech Republic, National Veterinary Research Institute in Poland, and the Norwegian Veterinary Institute in Oslo. The method yields test results in just 2 hours, using a type of mini-vacuum cleaner fitted with a special filter. This mini-vacuum cleaner collects the bacteria in the broiler house. The filter is then purified for total DNA and run in real-time PCR equipment. The PCR results indicate both the presence of, as well as the level of Campylobacter bacteria present in the dust of the chicken house. The test was developed collectively by the consortium, but the basic idea was initially developed and published by DTU back in 2009 (Olsen and others, Applied and Environmental Microbiology).

Chicken study probes resistance to Campylobacter

Chicken study probes resistance to Campylobacter

Receiving gut microbes from resistance chickens does not lessen chickens’ susceptibility to bacterium that causes food poisoning.

Only for closed sheds

The researchers conducted comprehensive field trials over a 2-year period which showed that the new method quadruples the likelihood of detecting Campylobacter in a chicken flock. That is up to 4 times more chicken flocks showing signs of Campylobacter when compared with sock samples. According to the Danish Professor, the new air testing system is useful in closed systems. He emphasizes that the system is only suitable for biosecured broiler houses where the inflow and outflow of air is regulated and the entire shed is a closed system with limited access.

The capacity of this air testing system is based on the number of air samplers (AirPort, Sartorius), but even with only 1 air sampler, a farm of up to 16 sheds can be tested in just 1 day. The way it works is that the air samples suck up to 750 litres of air during 15 minutes of continuous testing. The air filter may be obtained for as little as € 1 per filter, while the air sampler, which is similar to a hand-held vacuum cleaner, costs approximately € 2000 (from Sartorius). The filter samples are then treated for DNA purification (€ 3 per sample), which is tested in a PCR (€ 6). In total, this amounts up to only € 10 for a complete test result which covers an entire chicken house of up to 50,000 chickens for the entire 6 weeks of a production cycle. Compared to this, the sock method involves selective culturing, selective plates, and PCR or biochemical verification, the cost of which may even run to € 50 per sock sample.

Air sampling already on the market

The air sampling system is already on the market. It is available from the German company Sartorius. If needed, a complete setup can be supported by the Danish consultancy company AirSampler Aps (www.arisampler.dk). According to the Danish Professor, with the current, quick development of new technologies, sampling systems which are more sophisticated could soon become available. “However, such sophistications would compromise the simplicity and practicality of the system. One example is nano-chip devices that are used in highly specialised labs. Although interesting, they are also more prone to background noise usually found in such environmental samples.”

Farm Report: How a Dutch broiler farmer eradicates Salmonella

Farm Report: How a Dutch broiler farmer eradicates Salmonella

Dutch broiler farmer Ad Jansen (54) got rid of a persistent Salmonella infection by applying multiple measures.

Future is in test packages

The new air testing system offers even more benefits in addition to this. In the future it could also include Salmonella, avian influenza or other pathogens in a single testing package that uses the same filter sample for multi-purpose pathogen detection or antibiotic testing. The applications are almost limitless, the Professor believes, as long as we can catch the pathogen in the air or dust and convert it to substances that are detectable with amplification techniques.

One of the issues that animal producers are often concerned about is that sensitive tests detect pathogens that in reality do not exist: the issue of false-positive results. Professor Hoorfar: “But here we have shown that Norwegian flocks were completely negative in our sensitive test. Norway is known to have a very low prevalence of Campylobacter in chicken.” The lesson is that although the test is 4 times more sensitive, it still finds no Campylobacter where it should not. This is definitely a crucial point.