Avian Influenza detection using smell

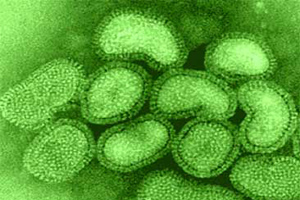

New research from the Monell Chemical Senses Center and the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) reveals that avian influenza, which typically is asymptomatic, can be detected based on odour changes in infected birds. The results suggest a rapid and simple detection method to help prevent the spread of influenzas in avian populations.

In a recent study published in the public access journal PLOS ONE, scientists examined how infection with avian influenza (AIV) alters faecal odours in mallards. Using both behavioural and chemical methods, the findings reveal that AIV can be detected based on odour changes in infected birds.

“The fact that a distinctive faecal odour is emitted from infected ducks suggests that avian influenza infection in mallards may be ‘advertised’ to other members of the population,” notes Bruce Kimball, PhD, a research chemist with the USDA National Wildlife Research Center (NWRC) stationed at the Monell Center. “Whether this chemical communication benefits non-infected birds by warning them to stay away from sick ducks or if it benefits the pathogen by increasing the attractiveness of the infected individual to other birds, is unknown.”

In the study, laboratory mice were trained to discriminate between faeces from AIV-infected and non-infected ducks, indicating a change in odour. Chemical analysis then identified the chemical compounds associated with the odour changes as acetoin and 1-octen-3-ol.

The same compounds also have been identified as potential biomarkers for diagnosing gastrointestinal diseases in humans. Kimball and colleagues hypothesize that metabolites resulting from viral infection interact in concert with bacteria in the gastro-intestinal system of ducks to produce “odour signatures” indicating presence of the AI virus.

“Avian influenzas are typically asymptomatic in ducks and waterfowl. Infection in these species can only be diagnosed by directly detecting the virus, requiring capture of birds and collection of swab samples. Our results suggest that rapid and simple detection of influenzas in waterfowl populations may be possible through exploiting this odour change phenomenon,” said Monell behavioural biologist Gary Beauchamp, PhD, also an author on the paper.

Future work will assess whether odour changes can be used for surveillance of AIV in waterfowl. In particular, researchers are interested in whether the odour change is specific to the AIV pathogen or if it is merely a general response to a variety of pathogens normally found in birds. Other studies will explore communicative functions of the AIV odour to gain greater understanding of how odours can shape social behaviour in wildlife populations.