Pheasant hunting boosts bird demand across North America

Hunting pheasants is big business across the United States and Canada pushing demand for the game birds sky high. Poultry World visits a pheasant farm to learn more.

On top of the huge demand for hunting, pheasant meat is also very popular with North American consumers which is good news for those who farm the birds. Pheasants are not indigenous to the United States – the first pheasants imported from Great Britain were in the late 1800s. Shipments of eggs continued to be imported into the US right into the early 1900s as it was soon discovered that pheasants thrived well there. By the 1920s pheasant populations were sufficient to be able to sustain hunting and thus a lucrative pheasant hunting sport began which has become very popular.

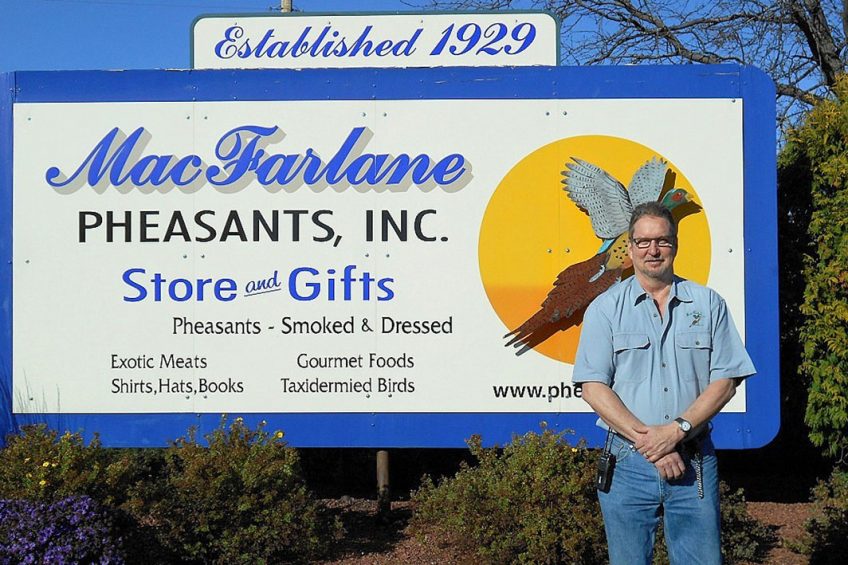

Farm profileBased in southern Wisconsin, USA, MacFarlane Pheasants Inc has been producing birds since 1929. Originally founded by Kenneth MacFarlane and later taken over by his brother Donald following an untimely accident that claimed Kenneth’s life. It is the largest pheasant farm in North America and will hatch almost 2 million pheasants this year along with 250,000 partridges. However, maintaining a business of this scale does not come without its fair share of challenges. |

Donald’s son, William MacFarlane – or Bill, for short – returned home right after graduating from college in 1979 to run the farm and is now CEO of the company.

“Our farm extends to 250 hectares overall,” Bill said. “Around 100 of those hectares are laid out in pens covered with netting. We have over 80 full-time employees working for us on the farm and in the processing unit.

“In 2019 we will hatch 1.8 million pheasants and 250,000 partridges. The pheasants produced are primarily ringneck, but about 250,000 are white pheasants raised for meat. Ringneck pheasants are sold live for hunting at 22 weeks old and above. The white pheasants are processed at a target weight of 1.8kgs at 12 weeks old,” he continued.

Biosecurity is a challenge but we have written biosecurity plans in place and are ready to act should the need occur.” – Bill MacFarlane.

Wide variety of birds

The farm raises a variety of birds including Chinese Ringneck Pheasants, Manchurian Ringneck Cross Pheasants, Kansas Pheasants, and Chukar Redleg Partridges. Over the years pheasants have also been imported from the wild in China and the farm has retained this wild stock bloodline in some of its birds today. Feeding all these birds comes at a cost but one that is manageable for the team at MacFarlane Pheasants. Bill explained there are bigger concerns on the farm than rising feed costs.

“We feed all the birds a diet consisting of corn, soy and wheat. A 20% protein-fortified grower diet would cost about US$ 0.26/kg. However one of the financial costs of more concern on the farm right now is the rising cost of employment. The basic wage is $ 13 per hour plus benefits, including health care and vacation.”

Producing hunting to processed pheasants – efficiency is key

Raising the birds for market efficiently is the main goal of MacFarlane Pheasants, thus helping to boost the farm’s profits. “Our major market is hunting reserves and we also have a business selling processed pheasants for food,” said Bill.

“Annually, we sell over 500,000 live mature pheasants and partridges for hunting and over 200,000 processed pheasants. We sell a live adult bird for about $ 14 on average. Dressed birds are sold by weight. The current cost to raise birds is just slightly less than the price we can sell them for. Our margins are therefore very tight.”

Our main challenges currently are the cost of labour and the availability of labour here in the US.” – Bill MacFarlane.

Bill raises his birds both indoors and outdoors depending on their age and the market requirements.

“The birds we produce for hunting are raised indoors for about 6 weeks, and then moved to outside pens after that,” he explained.

“Our meat birds are raised in the summer similar to the hunting birds in the pens. Our meat birds are produced all year round, so in the winter time they are raised indoors to the desired market weight.”

Not without its challenges

Avian influenza

“Biosecurity is a challenge but we have written biosecurity plans in place and are ready to act should the need occur. We do our best to not attract waterfowl to our farm by not having any ponds nearby, for example.”

“We have not had Avian Influenza here on our farm, thank God. However, we have got caught up in embargoes and restrictions on movements because of AI outbreaks that occurred quite some distance away from our farm,” he added.

Controlling predators

Controlling predator attacks at MacFarlane Pheasants is another challenge for Bill and his team who take preventative action to try to avoid such incidents. “We actively trap our perimeters for 4-legged predators such as coyotes and raccoons,” Bill said. “We also strive to control stray pheasants that escape which limits winged predators’ interest in our farm.”

Labour

“Our main challenges currently are the cost of labour and the availability of labour here in the US. We sell pheasants across the US and Canada. However the ability to transport live pheasants long distances is a challenge, weather wise, as well as logistically and labour wise. However, one of our biggest advantages is our solid reputation and longevity. Our location in the upper Midwest of the United States puts us at the heart of the demand for pheasants.” he concluded.